From rogue taxis to Diego’s grave, tracing art, memory, and spirit through Roma Norte

|

| Plaza Río de Janeiro |

Amy and I parted ways on Monday, June 30, under the bright sun of Oaxaca. She flew north to Minneapolis–Saint Paul, where her son Esau welcomed her with open arms. Her other son, Jess, and sister, Carrie, are close by—family warmth to soften the distance between Minnesota and Oaxaca.

I, meanwhile, came to Mexico City and find myself tucked into a quiet apartment in Roma Norte. A pleasant surprise. Tree-lined streets, bohemian cafés, artful storefronts. It feels safe, relaxed, alive. The kind of place where time breathes a little easier. And an artist fits in naturally.

Each day, I set out with camera in hand. I visited the Museo Soumaya—its silver, twisting architecture always catches the light just right, like a seashell turned toward the sun. Built by Carlos Slim and named after his late wife, the museum is a monument to both love and wealth. The collection isn’t quite world-class, but it’s deep, eclectic, and free to all. I admire that—art offered without charge, a gift from one of the world’s richest men to the people of Mexico.

Later, I did find the wedding district, tucked in a gritty part of town—rows of shops bursting with ruffled dreams: gowns for little girls, glittering tiaras, satin shoes no bigger than your hand. The shopkeepers were kind. I wandered timidly, a gringo in a bastion of Mexican culture—but left feeling part of something grand, and with some fine photos.

Next day, the metro dropped me too far from the Panteón de Dolores, so I caught a taxi the rest of the way. There was no entry fee, but most of the cemetery was closed to the public—only the Rotonda de las Personas Ilustres was open. Photography was limited to handheld devices, a gesture of reverence. Inside the rotunda, I stood beside Diego Rivera’s grave. The great muralist rests among kindred spirits—writers, painters, musicians, and revolutionaries. The Rotonda is a place where Mexico honors its luminaries—those who shaped the nation’s art, identity, and soul. It’s fitting that Diego lies there, surrounded by a chorus of voices that once stirred the heart of Mexico.

|

| Rivera Grave, front and back |

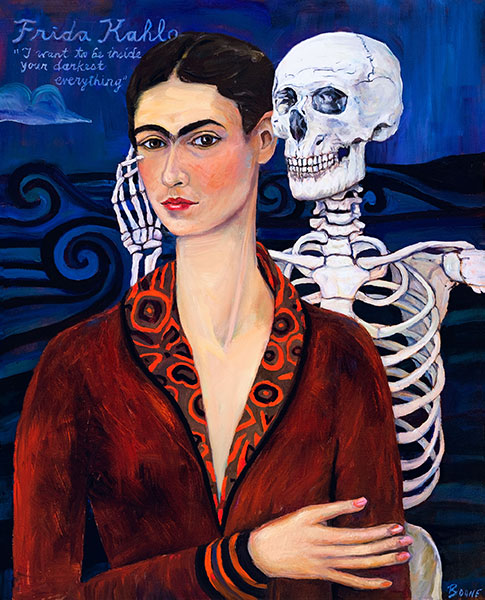

That very afternoon, as if guided by some invisible thread, I found myself face-to-face with Las Dos Fridas at the Museo de Arte Moderno. Kahlo’s most famous painting—created after her agonizing breakup with Diego—is raw, haunting, and unforgettable. Two versions of Frida sit side by side, hearts exposed, one bleeding onto a white dress. The work is both deeply personal and universally human—a portrait of love, loss, and fractured identity. Frida and Diego, both in one day. Icons in the annals of art, heroes in the heart of Mexico. Soulmates, despite it all—and now, both immortalized not just in memory and museums, but on Mexican currency as well.

The day held these highlights, yet I came home shaken. The taxi incident had rattled me. And the next day, July 5, was tender. It’s Naomi’s birthday in heaven. I spent the day quietly—sweeping, cooking, walking to the market. Praying. Tuning inward.

Health slows me—prostate issues bring discomfort and shadows of worry—but I press on, grateful for each step, each glimpse of the dream unfolding.

More and more, I long to surrender completely to spirit. To let go of striving. To live inside peace, with equanimity, and give myself entirely to God.

|

| Street Art |

Everywhere I walk, the walls speak. Mexico City’s street art is bold, defiant, and alive—murals, stencils, and graffiti bursting with color and voice. I’ve taken scores of photos, drawn to the visual symphony unfolding on every corner. Torn posters layered one over another become accidental masterpieces—an abstract collage of texture, pigment, and time. It's as if the city itself is constantly repainting its soul in public.

|

| "Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central," Diego Rivera, 50 feet wide |

Today, Sunday, with camera slung over my shoulder, I walked to the Centro Médico metro station, descended into the city's undercurrent, and boarded a train—intending Bellas Artes but momentarily spirited in the wrong direction. A swift correction, and soon I emerged into the heart of Centro, where broad pedestrian promenades unfolded beneath towering architecture and a blue Mexico City sky. I returned to the Museo Mural Diego Rivera, drawn again to “Sueño de una tarde dominical en la Alameda Central”—that dense dream of Mexican history and myth. It held me, as always, in its spell. Along the way and all the way back, I made photographs—faces, shadows, signs, surprises—collecting fragments of the city's restless poetry.

In a few days, on July 9, I’ll leave Mexico City and fly to Albuquerque. There, I’ll spend the night with my beloved daughter Sarah—always a joy and a grounding presence. The next morning, I’ll head to Santa Fe, where I’ll settle in for a few weeks of quiet living and renewal. Amy will meet me there, and before long, we’ll journey back together to our sweet Oaxacan home—where life is unhurried, and the dream continues.